Where the Wild Things Are

Growing up in rural Michigan, a few miles from DeWitt, I saw lots of fence rows grown up with trees and shrubs that had been planted by passing birds or the wind. Many farms had an area where a building had been allowed to fall into disrepair and foliage grew up through the holes in walls or roof. As farming gradually shifted from many small farms to fewer and larger farms, a lot of areas were cleared and leveled for access with ever-larger equipment. Now it is rare to see wild or unmanaged areas even in rural settings, but a few still exist.

Something I didn’t really think about until later I had further education in agriculture and the environment where the varied species I thought was native or had wild origins. Most of those plants and trees that are not native, but introduced into the environment.

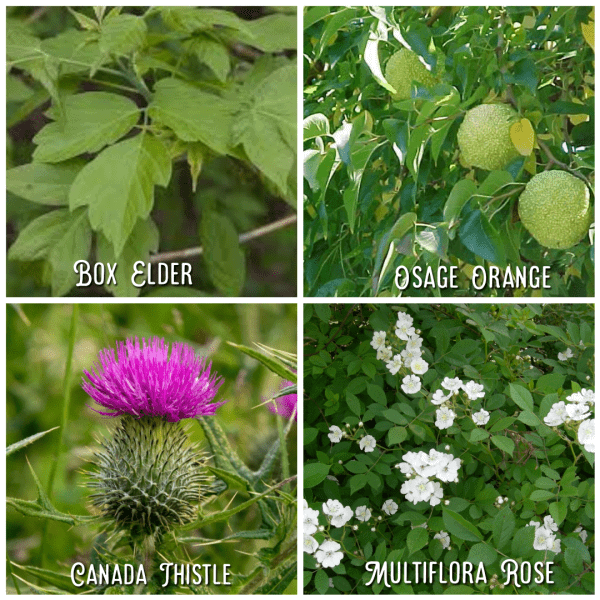

For the most part, the species that produced the most seed and were quick to grow in disturbed land that was not being farmed. One of those native species is the box elder.

Settlers often planted the box elder in for a quick growing shade tree. The seeds were easy to carry and store. Once established, they tolerate drought.

Today, maple trees provide most of our maple syrup. At one time, the box elder was tapped for maple syrup. The box elder bug, which favors this tree, as well as maple and ash trees, is one reason the box elder is seldom planted now. The box elder bug continues as an undesired, native invasive tree pest, and includes mid-Michigan.

The Osage Orange or Hedge Apple, is another tree native here in the U.S. This small tree was commonly used on farms for creating dense hedgerows. Originating in Texas, Oklahoma and Arkansas, the plant came from an area that was home to the Osage tribes, for whom the plant was named. It became common throughout the Midwest over the late 1800s and early 1900s. The branches would root easily and could be planted like a stockade, forming an impenetrable fencelike barrier to contain livestock or keep deer out of the garden once a few years of growth was achieved.

These native plants found in fencerows are important, but many others are invasive imports. Burdock was imported from Asia, and is now very common in disturbed soils. Luckily, we can fight back by eating it. But once a burdock plant matures and blooms can set thousands of seeds into the atmosphere and start hundreds of plants in the near vicinity, or anywhere the burrs land after attaching themselves to people or animals.

Another non-native is the Canada Thistle, originating in Southeast Europe and Asia. This plant was brought down from Canada by French fur traders after being carried over from Europe.

The Multiflora Rose was once promoted by extension agents as a fencerow barrier and food supply for wildlife, but it quickly became an invasive problem. We had an entire field fenced in this, and I loved watching my horse carefully reach in with his big flexible muzzle and pick rose hips for a snack. New plants are constantly being introduced both intentionally and accidently. Some are useful, while others are problematic.

There is a wonderful resource called the Michigan Natural Features Inventory, developed between 1816 and 1856. There were many types of forest, grasslands and swamps, as well as rivers, streams, lakes and ponds, each with their own natural plant life. Virtually all the landscape we see now has been altered since the time of that survey. Virtually all mature woodlands have been logged. Thousands of acres of land were cleared for farming and building structures. Many rivers were diverted, ponds and wetlands drained, for development and to reduce the diseases such as malaria that were common here until the early 20th century. Malaria was not eliminated in the U.S. until about 1951. Mosquito controls and the draining of swamps was key in winning that battle.

Michigan is a beautiful state with many woodlands, wetlands and natural areas, though the plants and animals we see today are not all the same as those cultivated by Native Americans

When traveling about the state, take some time to notice the plant species you see, and learn a few facts about the plants that interest you, including where they originated and whether they are native here.